Selection of Oliver Sacks' Books Offered by Bookseller James Cummins

New York — James Cummins announces its latest offering: part of the Working Library of Oliver Sacks.

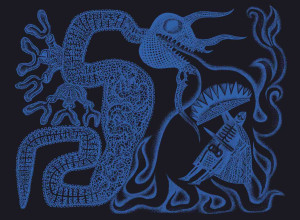

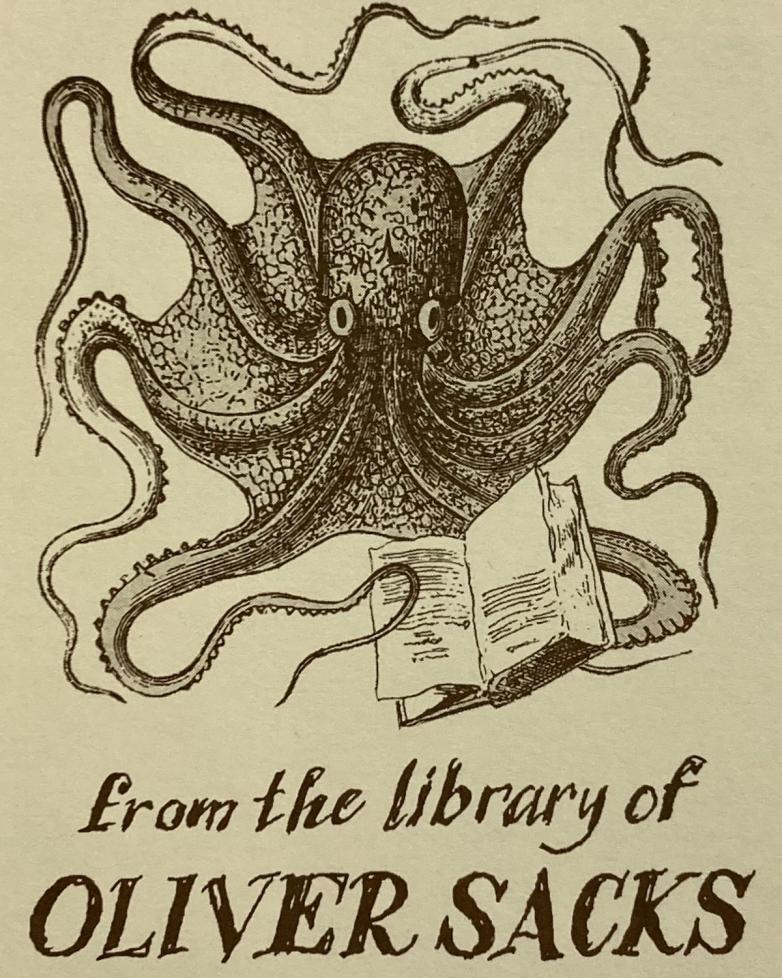

Like the tentacles of his octopus bookplate, Oliver Sacks’ interests were many and wide ranging. His library, offered here for the first time, gives a glimpse into the mind of the most widely read and respected neurologist since Freud.

With his best-selling book of essays, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, he brought the concerns of clinical neurology to an international readership, with nimbly phrased observations and the same compassion and kindness he accorded his patients. Sacks wrote about disorders and disability and their effects on individuals’ lives, including his own. His work brought forth adaptations for stage and television and other media, and his example inspired fellow scientists. Long a very private person, Sacks wrote about his life as a gay man in America, in the 1960s and beyond, in his autobiography On the Move (2015).

The library of Oliver Sacks, approximately 1,000 volumes, reflects his wide reading and many of the topics on which he wrote (some books are heavily annotated, often in the multi-colored felt tip pens he favored). He cherished his library and chose as his bookplate a design of a reading octopus.

Sacks was born into a medical family in London and was educated at St Paul’s School, where he met lifelong friends Eric Korn and Jonathan Miller (also a doctor and writer). All three were polymaths, or, as he wrote, “we were obnoxious, noisy, clever, Jewish boys”, keen on science and literature. Sacks had numerous uncles, one of whom inspired Sacks’ early interest in chemistry and about whom he later wrote in Uncle Tungsten (2001). Sacks studied at Queen’s College, Oxford, trained in medicine at the Middlesex hospital and graduated in 1958. In 1961 he came to the United States to train in neurology in San Francisco and at UCLA. From 1965 he was based in New York, affiliated with Beth Abraham hospital in the Bronx; he also held academic posts at New York University and Columbia.

His first book, Migraine (1970), was reviewed by W.H. Auden for the New York Review of Books, the first link in a long connection between Sacks and editor Robert Silvers, whose steady encouragement Sacks credited with making a writer of him. Sacks wrote some thirty essays for the NY Review over the years, even during his final hospitalization, where he examined his own experiences with clarity and wit. Some of the essays from the early 1980s, including “The Lost Mariner”, “The Twins”, and “The Autist Artist” formed the core of his widely acclaimed collection The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat (1985). There were many books after that.

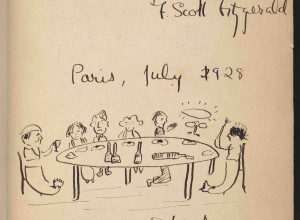

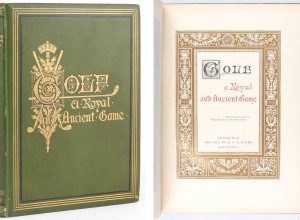

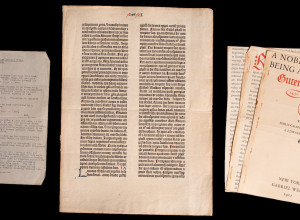

As a prominent neurologist and compassionate doctor, Sacks was esteemed by a wide array of colleagues. Many of his essays are magisterial examinations of the professional literature of the field and related aspects of medicine and philosophy. The library, comprising approximately 1,000 books, contains his marked working copies of many of the books discussed in the essays, presentation copies with reverential or affectionate inscriptions, gratitude for his advance comments used by publishers as cover copy or blurbs, as well as a variety of books on medical subjects, perception, evolution and other topics. Some books include Sacks’ ownership signature, a few of these dating back to his teenage and medical school years. A number of volumes have marks of other earlier owners, including Gilbert H. Glaser, M.D. (1920-2012), founder of the Department of Neurology at Yale.

In his essay “Remembering Francis Crick” (NY Review 24 March 2005), Sacks recalls how he read an advance proof of Crick’s The Astonishing Hypothesis “with great admiration and delight”. The library includes Sacks’ copy of the published book with an inserted inscription from Crick thanking Sacks for his comment (which appears on the jacket’s back panel along with a blurb from James D. Watson).

For his bookplate, Sacks had two designs prepared. The first was of a cycad, alluding to his book The Island of the Colour-blind and Cycad Island. “One summer after the war, in Bournemouth, I managed to obtain a very large octopus from a fisherman and kept it in the bath in our hotel room, which I filled with saltwater,” Sacks recalled his early interest in cephalopods in a chapter of Uncle Tungsten. He chose instead the image of a reading octopus, “which he adored”, as his friend and executor Dr. Orrin Devinsky recalls, and Sacks took great pleasure in affixing the bookplates into the books in his library.