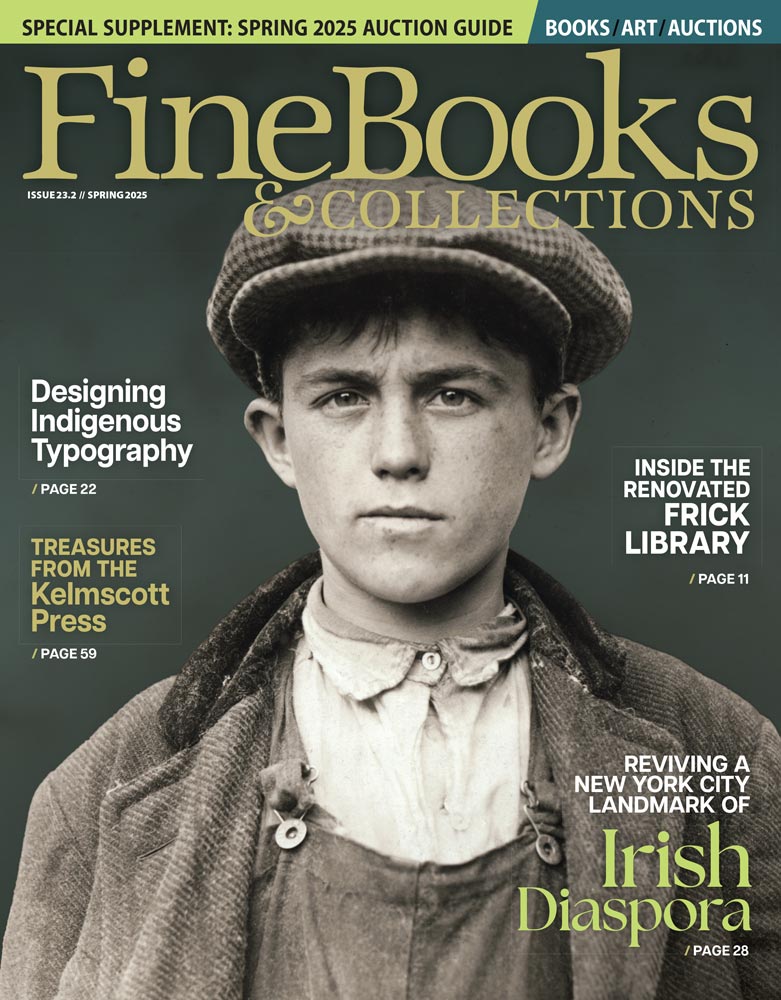

Woodcut Illustration and the Art of the Modern Book at The Morgan Library & Museum

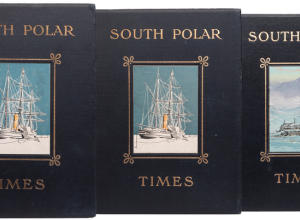

New York, NY, February 4, 2014—For a small but influential group of European and American artists engaged with the art of the book, the medium of the woodcut became an inspiration for stylistically diverse and provocative works in the decades surrounding the turn of the twentieth century. What many viewed as the detrimental and alienating effects of new illustration and printing technologies became a catalyst for artists to reinvent the book in creative expressions that elevated it to a work of art, and signaled the era’s meditative moments on the past and future of illustrated books and their makers. From the sublime Kelmscott Chaucer to the proto-graphic novels of Frans Masereel, woodcut illustration was integral to some of the most exquisite and innovative books of the modern age. These publications continue to delight the senses while prompting thoughtful explorations of the potential form and function of the printed book: how we read images and look at texts according to the hands that craft them.

Artists associated with the Arts and Crafts movement, such as William Morris, Charles Ricketts, Lucien Pissarro and Eric Gill explored the woodcut’s decorative and typographic properties expressive of their interests in the early history of the book and contemporary ideas of social reform. William Nicholson and Edward Gordon Craig adopted the aesthetics of archaic inexpensive forms of illustrated publications, updating chapbooks and almanacs with their fin-de-siècle styles. In France and Belgium, artists with ties to Paul Gauguin and the Symbolist movement, such as ?mile Bernard, George Minne, and Alfred Jarry, investigated the woodcut’s associations with religious imagery in books and popular prints, while Félix Vallotton, Edward Wadsworth, and Aristide Maillol cultivated the medium for original expression in artists’ books and avant-garde magazines. The medium’s semantic association with proletariat causes helped to shape the visual representation of American identity during the Great Depression in illustrations by Rockwell Kent and J. J. Lankes. In the final years of this period, often referred to as the woodcut revival, the medium’s democratic underpinnings and inscriptive properties were explored in works by Frans Masereel, Lynd Ward, and others, who exploited its potential for narrative expression through the wordless novel.

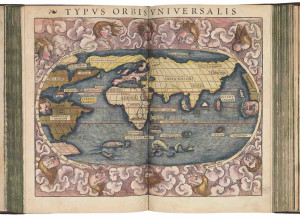

The more than ninety illustrated books, drawings, prints, and wood blocks in Medium as Muse: Woodcuts and the Modern Book are drawn almost entirely from the collection of The Morgan Library & Museum. The exhibition, on view from February 21 to May 11, surveys illustrated publications from 1890 to World War II, contextualizing them within their idealized past—in precursors and touchstones of medieval and Renaissance book design—and mapping potential trajectories in experimental animation, fine printing, and works by graphic artists today.

“Artists involved in the woodcut revival worked outside the mainstream, creating works at a transformative moment in the history of the modern book,” said William M. Griswold, Director of The Morgan Library & Museum. “New technologies, which may have threatened the viability of the craft of wood engraving, ultimately inspired a range of creative responses that used the printed book’s earliest form of illustration as a means to think through the relationship between a medium and its message—an idea with continuing relevance to artists today.”

The Exhibition

Historical Background: White-Line Revolution

The woodcut revival resulted from a convergence of factors but would have been unlikely without the Newcastle woodcutter and copper engraver Thomas Bewick (1753-1828). Historically, woodcuts consisted of black outlined designs created on the plank side of soft wood by removing the white areas with a knife or gouge, parallel to the grain. At the end of the eighteenth century, Bewick perfected a French method that used the metal engraver’s burin across the grain to create more delicate designs on Turkish boxwood. Strategically applying tools to its surface and laying paper underneath, he mimicked the tonal qualities of drawing by raising and lowering parts of the block and creating an intricate mesh of white and black lines that simulated shade, color, and a more naturalistic perspective just below the visual field. Harder boxwood, which would later withstand the pressure of new steam-powered printing presses, and the concurrent invention of smoother wove paper further facilitated the preservation of wood engraving’s finer lines. Within three decades, the book industry embraced Bewick’s effective and economic technique, ushering in the golden age of illustrated books.

Most of the artists in the exhibition used Bewick’s method, but some turned to the models of William Blake (1757-1827) and Edward Calvert (1799-1883), whose designs did not seek to emulate drawing or metal engraving, exploiting instead the medium’s limitations for artistic use.

The Ideal Book

In a period much like our own, the end of the nineteenth century was viewed by many as a moment of crisis for the book. Wood engravers’ skillful interpretations of artists’ designs had helped fuel the proliferation of illustrated printed matter, but their stylistic approximations of drawing soon devolved into a predictable pattern of mechanical lines and cross-hatches. With their interpretive role diminished to mere reproduction, engravers found themselves in competition with new photography-based technologies, prompting critics such as John Ruskin (1819-1900) to view the arts of the book and its craftsmen as casualties of the industrial age.

Leaders of the Arts and Crafts movement echoed Ruskin’s indictments of modern illustration, drawing parallels between machine-made books and the displaced workers of the mechanical age. As part of a broader project of aesthetic and social reform, they endeavored to reverse the book’s decline by founding small presses that took medieval and Renaissance books as their models. Woodcuts were essential to what William Morris (1834-1896) called “the ideal book”—a democratic vessel with which to convey beauty through the harmonious integration of image and type. Morris’s contemporaries and his successors adopted other models for similar ends, incorporating Art Nouveau elements and color under the influence of Japanese Ukiyo-e color printmaking, which had been masterfully adapted by children’s book publishers. Recrafting the handmade book for the modern age, they elevated it to a work of art and set design standards still in use today.

Picturing the Modern

Woodcut illustration, used by members of the Arts and Crafts movement to artfully unify image, ornament, and type, inspired other modern artists to explore its incongruous effects: a disharmony, reflective of the disjointed experience of modern life, articulated through the use of the medium’s primitive pictorial vocabulary and a semantic obscurity still tied to religious imagery and outmoded forms of popular literature.

Many artists rebelled against the refined qualities of modern wood engraving, embracing instead the look, terminology, and method of the early woodcut, as it appeared prior to Bewick’s innovations.

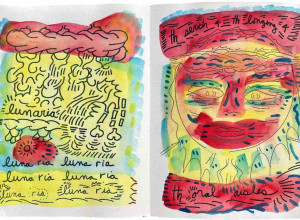

They conjured the chapbooks, broadsides, and religious prints of centuries past in experimental gestures of appropriation, pastiche, and collage. The woodcut’s association with simpler forms of communication for the masses encouraged its divergent use in both avant-garde movements and American advertising, appearing in a spectrum of formats—from deluxe artists’ books to small press publications and paperbacks. These varied approaches all emphasized the woodcut as a medium for original artistic expression and a rejection of illustration’s subordinate role to type and text. In the hands of modern artists, the medium became a muse for thoughtful examinations into the nature of imagery and its circulation, played out on the pages of the printed book.

Stories Without Words

Inherent in the gesture of wood engraving is the act of inscription—a connection between the unmediated, permanent mark of the artist’s hand on wood and a form of writing. This relation, first articulated by Ruskin, is prefigured in early block books and the woodcut sequences of Hans Holbein (1497-1543) and Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), resurfacing more provocatively in Bewick’s wood-engraved thumbprint and signature. Renowned for his sensational talent for depicting crowds, Félix Vallotton’s woodcuts pushed the metaphor of writing-engraving toward silent narratives of action or repose that seemed to capture in a moment the sounds, sights, and motion of modern life within the mute confines of a block. In 1918, the Belgian woodcut artist Frans Masereel merged Vallotton’s narrative skills with Expressionistic elements, allegory, and a quasi-autobiographical stance in his invention of the wordless novel.

Wordless novels are coherent narrative works comprising individual prints bound together, intended to be “read” in sequence. Flourishing between the world wars, the genre attracted a small number of American and European artists who favored the democratic mediums of the woodcut and printed book as the appropriate means to relate the modern individual’s struggles. Most woodcut novels were inflected with the era’s radical pacifism, socialism, and humanitarian concern for workers. The structural and visual similarities with early cinema were not lost on contemporary critics, who likened the experience of reading a novel in woodcuts to controlling the speed of the frames projected at a private screening of silent film.

Contemporary Trajectories

The exhibition concludes with a small selection of contemporary artists and bookmakers who have emulated, or expressed a significant debt to, the artists and ethos of the woodcut revival: Barry Moser, Gaylord Schanilec, George A. Walker, Eric Drooker, and Art Spiegelman.

Media and Interpretation

In addition to works by these and many other artists associated with the woodcut revival, the gallery installation will include an area entitled Woodcuts 101 with rudimentary materials and preliminary designs by Gustave Doré, Walter Crane, and Edward Burne-Jones to point to some of the ways works were transferred to wood blocks. The display also includes wood blocks and electrotypes associated with Doré, Thomas Bewick, and Frans Masereel, as well as Rudolph Ruzicka’s key and color blocks and progressive proofs that illustrate the process of color printing.

These introductory materials are supplemented by a short archival film in the gallery by Elias Katz that documents American wood engraver Lynd Ward in the act of designing, engraving, and printing from a wood block for his 1937 wordless novel Vertigo.

Adjacent to the wordless novel case, a touch screen will sample short narrative sequences from works on view by Frans Masereel, Lynd Ward, Otto Nückel, and George Walker.

Berthold Bartosch’s 1932 experimental animated film L’Idée: sa naissance, sa vie, et sa mort, based on Frans Masereel’s 1920 novel in woodcuts of the same name, will be shown on a nearby LED screen.

PUBLIC PROGRAMS

Discussion

Art Talk: Contemporary Responses to the Woodcut Revival

Barry Moser and Gaylord Schanilec

Wednesday, April 2, 6:30 pm*

Acclaimed contemporary wood engravers Barry Moser and Gaylord Schanilec discuss with curator Sheelagh Bevan the revival of woodcut illustration and how this transitional moment in the history of the modern book informs their own practice today.

Tickets: $15; $10 for Members; Free for students with valid ID

www.themorgan.org/programs; tickets@themorgan.org; 212.865.0008 x 560

*The exhibition Medium as Muse: Woodcuts and the Modern Book will be open at 5:30 pm for program attendees.

Gallery Talk

Friday, March 7, 6:30 pm

Sheelagh Bevan, Assistant Curator, Printed Books and Bindings, will lead this tour of Medium as Muse: Woodcuts and the Modern Book.

All gallery talks and tours are free with museum admission; no tickets or reservations are necessary. They usually last one hour and meet at the Benefactors Wall across from the coat check area.

Family Program

Making Art in Reverse: Printing for the Family

Saturday, March 15, 2-4 pm

Learn how to draw backwards to make it look right! Following an introduction to the art of woodcut book illustration in the exhibition Medium as Muse: Woodcuts and the Modern Book, families will experiment with simple printing techniques, laying out images in reverse to create a composition that they will print. Bring a favorite poem to include in the art project.

Tickets: $8, $6 for Members, $2 for Children

All Family Programs are appropriate for ages 6-12. Workshops are for families with children, with a limit of two adult tickets per family.

Film

O Brother Man: The Art and Life of Lynd Ward

Friday, March 28, 7 pm

(2012, 90 minutes)

Director: Michael Maglaras

Featuring more than 150 of Lynd Ward’s wood engravings, drawings, and illustrations, this new documentary from 217 Films brings to life the creativity of one of the most prolific book illustrators and printmakers in the history of American art and illustrates his mastery of “the novel without words.” New York premiere, with an introduction by the filmmaker.

Exhibition-related films are free with museum admission. Advance reservations for Morgan Members only: 212.685.0008, ext. 560, or tickets@themorgan.org. Tickets are available at the Admission Desk on the day of the screening.

Tour

Between the Lines Tour

Saturday, April 5, 11 am

Written or drawn, lines are to be read and interpreted. In this interactive gallery talk, a Morgan educator will lead visitors in an hour-long discussion on a selection of works from Medium as Muse: Woodcuts and the Modern Book.

All gallery talks and tours are free with museum admission; no tickets or reservations are necessary. They usually last one hour and meet at the Benefactors Wall across from the coat check area.

Adult Program

Introduction to Woodcut: Hands-on for Adults

Friday, April 18, 6-9 pm

This workshop will give adults a chance to experiment with woodcut techniques as illustrated in the exhibition Medium as Muse: Woodcut and the Modern Book. After a introductory tour of the exhibition by Morgan curator Sheelagh Bevan, artist Barbara Henry will lead participants in a hands-on exploration of the medium’s characteristics.

Tickets: $20; $15 for Members

www.themorgan.org/programs; tickets@themorgan.org; 212.865.0008 x 560

Organization and Sponsorship

The exhibition is organized by Sheelagh Bevan, the Morgan’s Andrew W. Mellon Assistant Curator in the Department of Printed Books and Bindings.

This exhibition is made possible by the Charles E. Pierce, Jr. Fund for Exhibitions, Fern and Hersh Cohen, the Ricciardi Family Exhibition Fund, the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation, and Robert Dance.

The programs of The Morgan Library & Museum are made possible with public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council, and by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature.

The Morgan Library & Museum

The Morgan Library & Museum began as the private library of financier Pierpont Morgan, one of the preeminent collectors and cultural benefactors in the United States. Today, more than a century after its founding in 1906, the Morgan serves as a museum, independent research library, musical venue, architectural landmark, and historic site. In October 2010, the Morgan completed the first-ever restoration of its original McKim building, Pierpont Morgan’s private library, and the core of the institution. In tandem with the 2006 expansion project by architect Renzo Piano, the Morgan now provides visitors unprecedented access to its world-renowned collections of drawings, literary and historical manuscripts, musical scores, medieval and Renaissance manuscripts, printed books, and ancient Near Eastern seals and tablets.

General Information

The Morgan Library & Museum

225 Madison Avenue, at 36th Street, New York, NY 10016-3405

212.685.0008

Just a short walk from Grand Central and Penn Station

Hours

Tuesday-Thursday, 10:30 a.m. to 5 p.m.; extended Friday hours, 10:30 a.m. to 9 p.m.; Saturday, 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.; Sunday, 11 a.m. to 6 p.m.; closed Mondays, Thanksgiving Day, Christmas Day, and New Year’s Day. The Morgan closes at 4 p.m. on Christmas Eve and New Year’s Eve.

Admission

$18 for adults; $12 for students, seniors (65 and over), and children (under 16); free to Members and children 12 and under accompanied by an adult. Admission is free on Fridays from 7 to 9 p.m. Admission is not required to visit the Morgan Shop, Café, or Dining Room.