The Kelbaugh collection contains many pictures of African Americans, several made without the consent of their subjects, often to support white concepts of family, wealth, and status. Among these images are disquieting photographs of African American women shown attentively caring for their white charges while they were denied the ability to form their own stable family units. In one haunting picture of two young African American girls holding hands, a label pasted on the front states “Peculiar Institution”, the euphemism used by John C. Calhoun and other defenders of slavery in the South.

Other images were taken to aid abolitionist causes and sold to support the education of newly freed people; for example, the carte de visite entitled Wilson Chinn, a Branded Slave from Louisiana depicts a man wearing a spiked neck collar, ankle chains, and an iron leg brace. While the purpose of other photographs is not known, the picture of two men - one Black, one white - holding hands could reflect the widely embraced abolitionist slogan “Am I not a Man and a Brother?”

“As a young social studies teacher in the Baltimore County public schools some 50 years ago, Ross Kelbaugh recognized that he could use photographs as a springboard for learning in his classroom,” said Sarah Greenough, senior curator and head of the department of photographs at the National Gallery. “He knew that the numerous photographs of African Americans that he discovered as he built his collection, pictures that were largely overlooked by other collectors at the time, could engage his racially diverse students, allowing them to see that everyone’s past, as he has written, ‘is an integral part of this nation’s story of E pluribus unum, out of many, one.’”

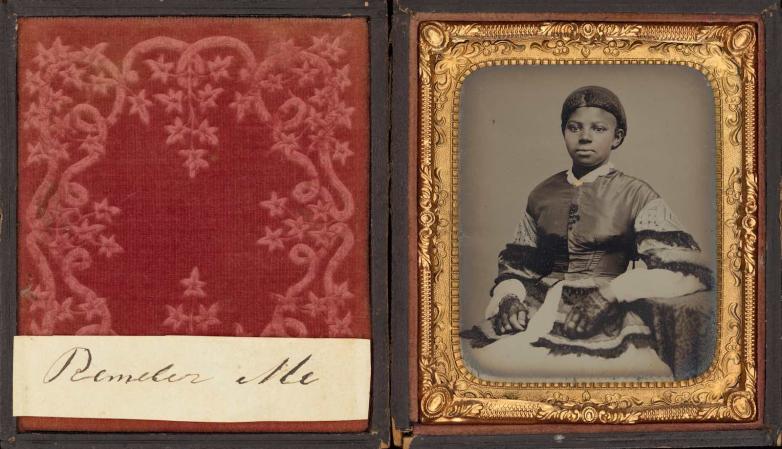

Most of the pictures in the Kelbaugh collection were made to bear witness to Black pride and accomplishment. Although the identity of several of the people depicted is unknown, their elegant clothing and determined, self-confident expressions suggest that they were freemen and freewomen eager to record their prosperity. Many were made to ensure that history remembered their subjects, such as the tintype with color applied by an unknown artist that included a slip of paper inscribed “Annie/Remember Me.”

Several images celebrate acts that were previously denied to African Americans. For example, an unknown Civil War soldier paid extra for the photographer to highlight with gold not only his ring, brass buttons, and belt buckle, but also his knife and revolver, which he, like other African Americans, had previously been prohibited from possessing. After Emancipation, in an important rebuttal to the practice of depicting enslaved women with white children, some prosperous African American women had themselves recorded with their own children, while others had their children depicted carrying haversacks, as if on their way to school, another right previously denied to African Americans. Still others depicted themselves with books, proudly projecting an air of defiance.

“After decades of collecting adventures, I am honored to have this portion of my photographic treasures now join the National Gallery of Art, where they can be studied and appreciated by everyone. These photographers and the people preserved in their photographs can finally become a permanent part of the American memory,” said Ross J. Kelbaugh.

The Kelbaugh collection also includes photographs of celebrated African Americans, such as Frederick Douglass and Josiah Henson whose courage and resilience inspired Harriet Beecher Stowe’s portrayal of the hero in her book Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Several pictures directly address the history of enslavement, such as depictions of the “Slave Pen” in Alexandria, Virginia (1861), enslaved people on Edisto Island (1862), and recently freed enslaved people on the Bullard Plantation, Louisiana (1864). Other pictures address Reconstruction, such as one of an African American cowboy and images from the Jim Crow era. The collection extends into the 20th century, with compelling portraits of distinguished African American members of the Knights of Pythias and World War I and II soldiers.