Book Chat with Leonard Marcus

Last week I had the opportunity to speak with Leonard Marcus, considered by many to be the leading authority on the history of children's books in America. He has written dozens of books, from biographies to histories to collections of interviews with authors and illustrators.

2013 has been busy for Mr. Marcus -he wrote an article about Maurice Sendak for the current issue of Fine Books & Collections Magazine, curated the current exhibit at the New York Public Library dedicated to children's books, and has a biography on Randolph Caldecott slated for publication next month. During our hour-long conversation we discussed these and other topics circulating in the children's book world. Below is part one of our conversation.

photo credit: Elena Seibert

What prompted you to put together this exhibit at the NYPL at this point in time?

The Library contacted me. They decided to do a show on children's books because the last one they had done was in the 1980's. A generation of children had come and gone, and the library felt that another exhibit was past due.

I think the library has changed in many ways - and so have many other cultural institutions. There is a greater interest in making rare materials accessible to the public, not just in the literal sense of putting them on display, but presenting them in a way that's less intimidating than in the past.

I think of the Metropolitan Museum and the first time I went there as a teenager. There was this atmosphere of reverence, and that has since changed. All cultural institutions, as a matter of survival, I think, are making the public feel more welcome and relaxed in the presence of their treasures. So the hope for us was to put together an exhibit that gives people ways of connecting with the books in a meaningful way.

Have you noticed this trend of accessibility in other institutions where you've put on exhibits?

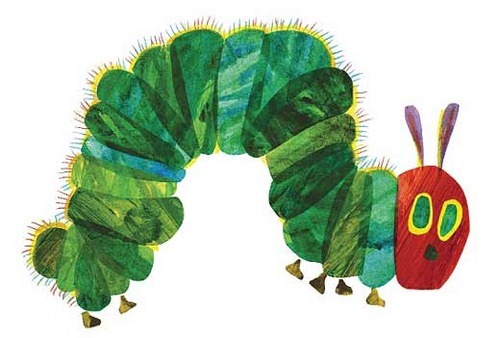

Well, I'm very involved with the Eric Carle Museum- I'm on the board of trustees - and I think that having a museum dedicated to children's books is a sign in itself of a break with tradition. In the past, museums would not have considered children's book art worthy of exhibition. Certainly not anything contemporary - perhaps old Victorian books that had acquired a certain patina. The Carle is dedicated to contemporary art that, to some extent, presents itself as museum for people of all ages. It makes provisions for the very young who might want to sit on a bench and be read to, or go into a room and create their own art. That is indicative of a shift of how museums view themselves and their role in society.

Does this also reflect a shift in the way parents read and share books with children?

I think that parents today belong to the best-educated generation in the history of the world, so I think they are very book-conscious. They're also more aware of how books are made and perhaps their children are as well. Now artists and writers and can be encountered at story hours, museums, bookstores.

Some parents, I think, are eager to expose their children to a wide range of books, it's a way of encouraging children in their own creativity. One of the hallmarks of Eric Carle, who works primarily in collage, is that he creates the kind of art children do when they are in preschool. One of the unspoken messages of Eric Carle's art is that, his work is not too different from art that children might create on their own.

That approach reminds me of what Mo Willems and Hervé Tullet spoke about during a recent talk at Books of Wonder in Manhattan

Mo Willems is all about making art that children can do themselves. It's about demystification. I think that's a really big theme in the museum world right now, and especially with my exhibit at the NYPL, the goal is to take things off the pedestal and to make people feel that, when we're talking about culture, we're talking about ownership, and that everyone can partake in it.

Some books on display at the NYPL were quite scary - the Grimm books, for example - and some contemporary parents might say 'I'm not going to read that to my child.' Yet on the flip side, there exists a genre of violent vampire and zombie books that many parents share freely with their middle-years children. Do you notice any sort of disconnect, or are we watering down children's literature?

Well some are for it, some abhor it. One good thing about the present is that there is such a range of books available. On the one hand we have a deeper awareness of child psychology than was reflected in the books published for children one hundred years ago. Fifty years ago there was still a desire to shield children from the darker parts of life. Then there are people like Maurice Sendak who really brought a new and frank insight into the equation, which had an impact on books of all kinds.

On the other hand there are intense commercial pressures brought about by the fact that publishers have consolidated, as well as booksellers. There is a rush for the lowest common denominator - the least offensive book that will appeal to the greatest number of people. So those pressures work against each other. Sometimes one wins out, sometimes the other does. I think that defines the current situation. I see a lot of very safe books, certainly when you look beyond the book world into the film world, such as with Disney, where the financial stakes are so much greater, to come up with something that's palatable rather than emotionally satisfying.

Parents must fit in here somewhere.

I think parents need to know that it's their responsibility and it can also be a great pleasure for parents to be involved in their children's reading. There's been some tendency to leave book choices to the experts, or alternatively to leave the child with a handheld device and then leave the room let the child to fend for himself or herself. That's perhaps the worst of all choices, because, in my opinion, the book you choose matters, the experience you have of the book matters even more. And for a young child, that experience needs to include an adult who can mediate the story, and assessing it with a loving attachment.

You don't sound like you are against the use of technology, rather in favor of its judicious employment.

I'm not against technology, but it's no substitute for a parent. And in certain respects, paper books function more effectively than e-books do. I think that these are two art forms that are going to both develop and each will put pressure on the other to do better at what it can do best. A Kindle, for example, can't change its format. Every picture book has to be exactly the same size to fit in the screen, and that is a real problem for creator of picture books, whereas the trim size and other physical aspects of the book have always been considered expressive elements. But that's not to say that some brilliant person couldn't take an e-book - which is really a form of animation - and do something on an aesthetic level that someone working in a picture book format could only dream of doing.

There's more! Read the rest here