The Literary Treasures of Troy

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898), Helen's Tears, drawing from The Flower Book, 1882-1898.

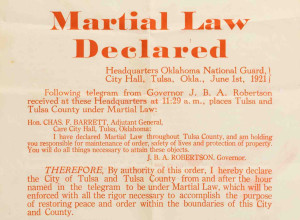

Troy: myth and reality at the British Museum is the first major Troy exhibition in the UK. While it concentrates on pottery, weaponry, and sculpture to tell the story of the Trojan War and its legacy in around 300 objects, the show also features a wealth of literary treasures associated with the well known legends as well as the discoveries made by archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann in Turkey in the 1870s.

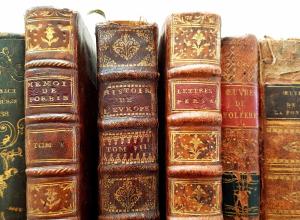

The two oldest written pieces date to the 1st century AD, part of a papyrus manuscript of the Odyssey with passages from book 3 annotated by ancient scholars, and from the same period, again on papyrus, a school pupil has written line 2601 from The Aeneid seven times in practice, “non tibi Tyndaridis facies inuisa Lacaenae,” referring to the role of Helen in the downfall of Troy ("not for you the hated face of the Laconian women, daughter of Tyndareus"). More pupil exercises are featured on a wooden board dating back to the Roman occupation of Egypt in the 5th century AD. These are also lines from the Iliad celebrating the joys of drinking. As historian Bettany Hughes says in her book, Helen of Troy: Goddess, Princess, Whore, it resembles a “swinging, Wild West saloon sign.”

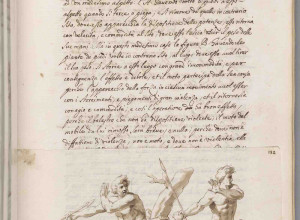

On display too is the Townley Homer from 1059 which not only includes the text of The Iliad, but also has many marginal notes and interlinear glosses. When this was last sold in auction, in 1814, it was bought for £620.

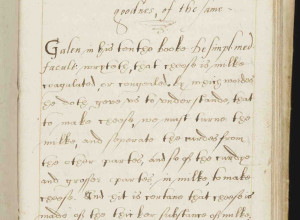

Among other early volumes in the exhibition are John Lydate’s Troy Book from around 1457-60, telling the story of Troy in Middle English thanks to a commission from the Prince of Wales, later Henry V; the first book ever printed in English, Recuyell of the historyes of Troye, published by William Caxton around 1474, possibly an inspiration for Shakespeare’s "Troilus and Cressida"; and Chapman’s Homer c. 1616, which John Keats memorably first looked into.

Also of interest is the English translation by John Dryden of The Aeneid from 1697. This was a very personal approach in which he made additions and changes, claiming optimistically that these expansions of Virgil’s work were “not stuck into him, but growing out of him.”

The exhibition runs to March 8, 2020. Visitors should remember to take their reading glasses as the signage is rather small and frequently at ankle height.