Faking It: Literary Forgery in Early Modern Europe

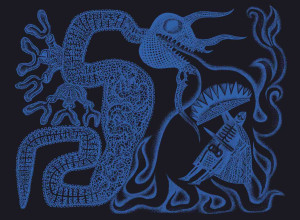

Literary forgers have plied their trade as long as there's been something worth copying, "creating" purely for financial reasons or simply being able to get away with it. Throughout history, some forgers have been content to "gild the lily," so to speak, while others attempted to rewrite history. Some fakes were so good they did alter history.

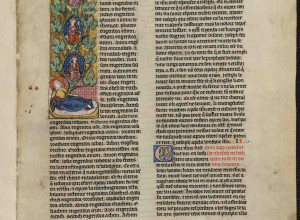

Notable literary hoaxes include a document in Emperor Constantine's hand circa 756 AD that donated land to the Catholic Church. Scholar Lorenzo Valla proved it was a fake in 1440, but the Church suppressed Valla's findings until 1929 when it finally returned the land in question to Italy.

Sometimes, forgers were seeking approval. In 1794, eighteen-year-old William Henry (W.H.) Ireland showed his bookseller father (and Shakespeare aficionado) a mortgage bearing the Bard's signature, which happened to turn up in the law office where young W.H. worked. More Shakespeare papers continued to miraculously appear out of this same office, including a love letter and a hitherto unknown Shakespeare play called Vortigern. The Irelands showed the script to a local theater operator, who smelled something fishy but went along with the charade, going so far as to stage it. But the actors, unwilling to play along, eviscerated it in its solo performance, thoroughly mocking Vortigern to the point that W.H. eventually confessed his forgeries. His poor father, meanwhile, insisted until his death that the discoveries were real.

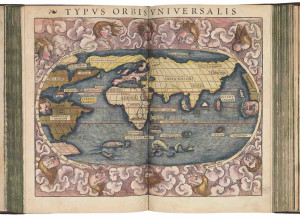

Even Renaissance antiquarians were duped by fabricated testimonies. French humanists like Francois Rabelais believed that Latin texts itemizing the existence of ancient Roman relics beneath modern cities were authentic. In fact, these bogus "revelations" were created by 16th-century forgers cashing in on humanists' desires to verify their noble Roman heritage.

Book collections have been intentionally built around forgeries as well--Arthur and Janet Freeman amassed over 1,700 volumes of literary fakes, dubbed the Bibliotheca Fictiva, which was acquired in 2011 by Johns Hopkins University. This collection inspired the recently published Literary Forgery in Early Modern Europe, edited by Walter Stephens, Earle A. Havens, and Janet E. Gomez (Johns Hopkins Press, $54.95). Thirteen essays composed by some of the world's leading humanities scholars explore the notion that early forgeries form their own literary genre and, rather than being derided as knock-offs, fakes are very much worthy of serious scholarship.

Book collections have been intentionally built around forgeries as well--Arthur and Janet Freeman amassed over 1,700 volumes of literary fakes, dubbed the Bibliotheca Fictiva, which was acquired in 2011 by Johns Hopkins University. This collection inspired the recently published Literary Forgery in Early Modern Europe, edited by Walter Stephens, Earle A. Havens, and Janet E. Gomez (Johns Hopkins Press, $54.95). Thirteen essays composed by some of the world's leading humanities scholars explore the notion that early forgeries form their own literary genre and, rather than being derided as knock-offs, fakes are very much worthy of serious scholarship.

Truth-twisting, outright fabrication, and efforts to uncover forgeries through history make for entertaining academic investigations, revealing the thin line between what's real and what isn't, and why so many people, from collectors to scholars, are willing to overlook inaccuracies.

Victorian art critic John Ruskin got it half right when he wrote in 1843 that, "the essence of lying is in the deception, not in words." Literary Forgery argues that it's both.