In his discussions, which included numerous specific examples of authors, titles, and collecting areas that have been widely pursued or ignored, Carter made no secret of his opinions, some of which were very firmly held. He felt that collections needed to have a central focus, and that collectors should educate themselves diligently in their chosen fields. Speaking and writing at a time in which institutional special collections libraries were being created and were growing at a rapid rate, especially in the United States, Carter also criticized the significant impact that the resulting increased (and well-funded) institutional demand had on the market for books that collectors had previously believed were their province alone.

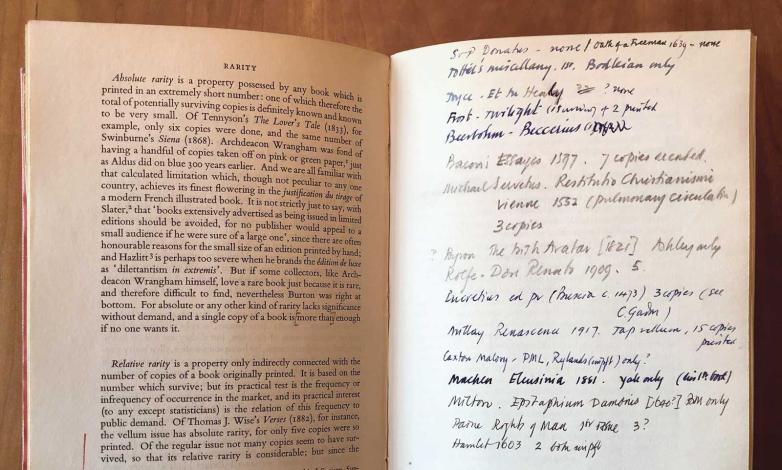

Though he recognized the role that sentiment played in book collecting, Carter also promoted the application of logic and reason to the decisions that collectors make in deciding what to collect, and the editions, bindings, or associations that collectors consider in deciding which copies to add to their collections. Carter also provided an extensive chapter-length discussion of the various types of rarity (absolute, relative, temporary, localized), along with another covering the wide-ranging area of condition, with a focus on the changing views held by collectors of what constitutes “original” condition, and a plea for reason and practicality in the pursuit of books that were issued in publishers’ bindings.

We live in a very different world than the cozy and insular collecting bubble depicted by Carter. As Jim Hinck has described in detail (see “Further Reading”), the Internet and the widespread international availability of books available for sale and information about them have created a collecting environment unknown to Carter, in which, for example, many of the concepts and categories of rarity that he detailed no longer apply. But there is still a great deal of valuable and thought-provoking material in Taste and Technique for anyone who is seeking something more than a how-to book on the subject.

For most modern readers, however, Carter does not yield up his wisdom easily. In addition to his widespread use of book collecting terms, there are hundreds of references to authors, titles, collectors, booksellers, bibliographies, catalogues, prices (both high and low), and many readers will need to keep a Google window open if they’re to have any idea of what Carter might be referring to. And then there are Carter’s numerous allusions and quotations, in which his classical learning is on full display, with the Greek and Latin words or quotes appearing in their original forms, with no translations provided. Colton Storm, who reviewed Taste and Technique for The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America (Volume 43, Number 1, First Quarter, 1949, pp. 90–91), noted “the author’s irritatingly supercilious style,” but Storm also wrote that “no book collector, amateur or adept, should be without a copy of Mr. Carter’s book.”

Larry McMurtry held an even higher opinion of the importance of Carter’s Taste and Technique, though he also recognized its limited appeal:

John Carter’s best book, in my view at least, Taste and Technique in Book Collecting, was initially delivered as the Sandars lectures in bibliography at Cambridge University in 1947. I don’t think that there is a better book about book collecting: the prose is splendid, the judgments acute, the suggestions reasonable. Yet I can’t really imagine anyone but a book dealer reading and rereading it, as I have done. The book-chat of even the most superior tradesman may make its strongest appeal only to those who practice the same trade. (“Mad About the Book,” in The New York Review of Books, December 20, 2001, pp. 57–59).

While it’s true that Carter’s frame of reference in Taste and Technique was a commercial one, it can and should be read and reread by collectors and special collections librarians as well as by booksellers. Anyone with a deep interest in rare books (including the ever-changing views of what constitutes a “rare book”), along with how these books have been collected, can gain immensely from a detailed study of Carter and the perspective that he provided. Book collecting has broadened and diversified considerably since 1947, and most collectors today don’t encounter incunabula when they visit a bookshop, nor do they have any idea of what a cancel, Strawberry Hill, or STC might be. Regardless of your preferred collecting fields, however, it’s eye-opening to read about how collectors of the past have formed their collections, and Taste and Technique explains a great deal about why some books are scarce and others aren’t, and why special collections libraries contain the books that they do.

I think I bought my first copy of Taste and Technique at Dawson’s Book Shop in Los Angeles in 1973. Though there was a great deal that I didn’t understand, I was fascinated by it on my first reading, and I’ve reread all or most of it every year since then, seeing new things and making new connections each time. If you’re seriously interested in rare books, so will you.