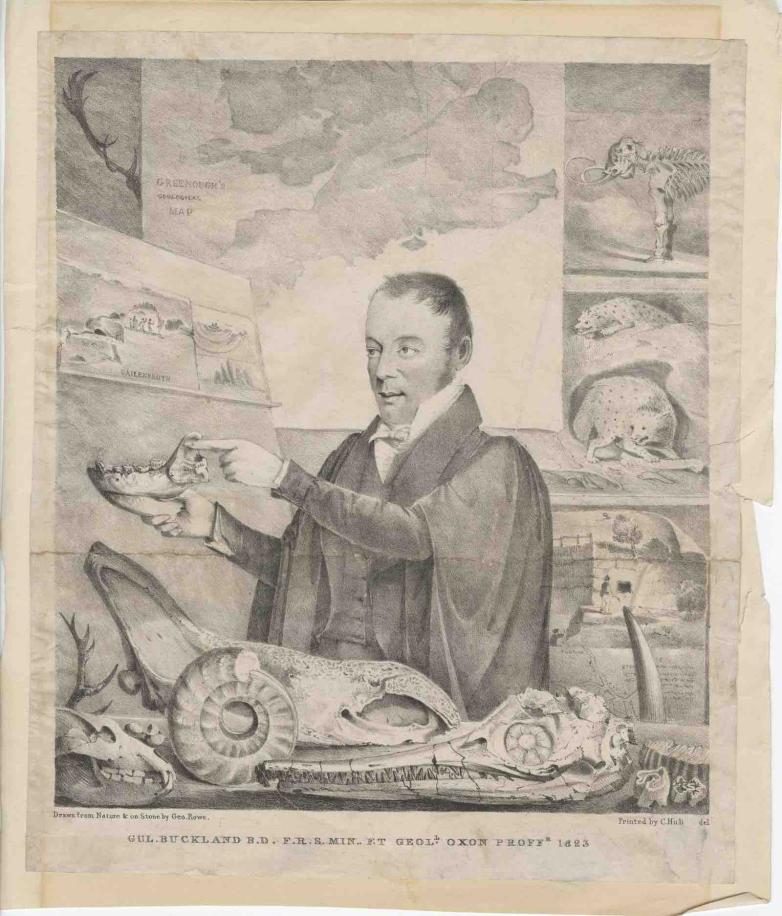

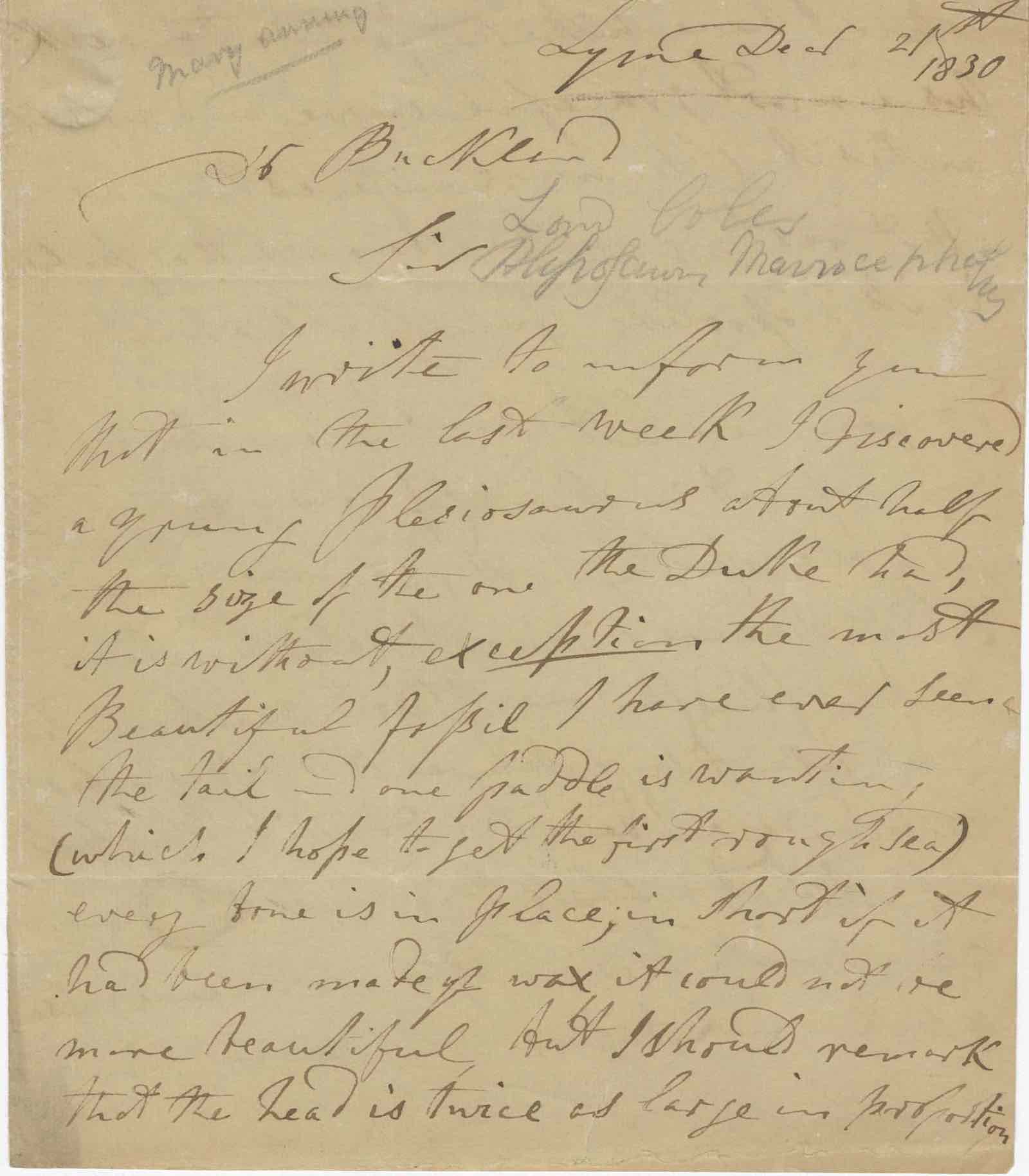

The archive reveals aspects of Buckland’s life as a student at Christ Church, as well his work as a practising geologist, university lecturer, and eminent churchman. Evidence from the archive provides detailed insight into the thinking and institutions of the early 19th century, a time when science and theology often gave different explanations for natural phenomena. Numerous letters on topics ranging from zoology and geology to aesthetics and administration demonstrate the diverse network of people connected with Buckland. They include correspondence with major figures such as art critic John Ruskin and prime minister Robert Peel.

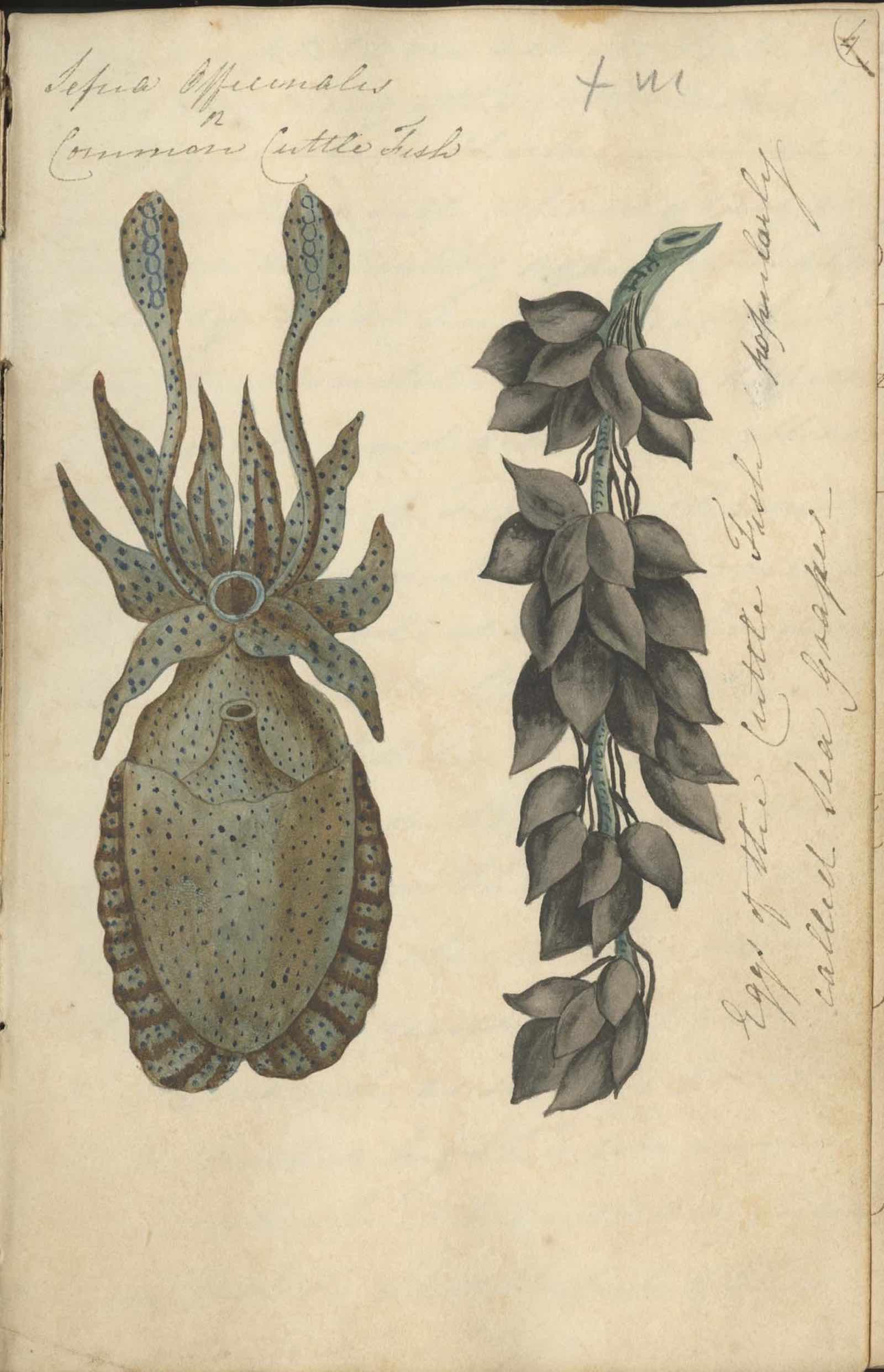

The archive also includes original artworks, such as Thomas Sopwith’s watercolour of William Buckland (previously thought to be a portrait of Mary Anning), and a rare, coloured version of the lithograph based on Henry de la Beche’s drawing Duria Antiquior – the first pictorial representation of a scene of prehistoric life based on fossil evidence.

Dr Simon Thurley CBE, Chair of the National Heritage Memorial Fund, said: “It is fantastic news that this collection can be shared with the public, providing an insight into the scientific thinking and institutions of early 19th-century England, as well as providing a rich and colourful primary account of Buckland’s life and career. It is also wonderful to see that the significant artistic and scientific contributions made by Buckland’s wife Mary (née Morland) are highlighted through this collection, as well as the important roles of other ‘invisible technicians’ such as quarrymen, collectors, preparators and replicators, presenting a fuller picture of those involved in natural science at that time.”

OUMNH is already the pre-eminent repository for Buckland’s archive and object collections, with existing holdings including extensive professional correspondence, lecture notes, and teaching diagrams, as well as more than 4,000 fossil, rock, and mineral specimens. The additional archive provides missing pieces of the jigsaw.